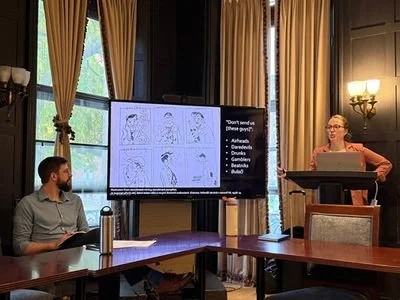

It was a delight to share my research with students and faculty at Boston University’s Frederick S. Pardee School of Global Studies a few weeks ago. I’m honored by the attention the students gave my work. You can read their write-up here: Global Security Series Welcomes Julia Mead to Discuss Mining, Masculinity, and Energy Security in Czechoslovakia

The 1970s Energy Crises and the Threat to Czechoslovak Consumer Socialism

A West German and an Austrian drive their Mercedes cars to Bratislava to fill up on gas. What could possibly go wrong? At long last, my article "The 1970s Energy Crises and the Threat to Czechoslovak Consumer Socialism," is out in the world.

New Article Published

I am so excited to have had an article published as part of a special issue of the journal Connexe about gender and material culture in Eastern Europe. My article, “The Kingdom of Antique Televisions: Reparability, Masculinity, and the Afterlives of Socialist Electronics” is open access.

Podcast Interview

I really enjoyed returning to the Actually Existing Socialism podcast to discuss my PhD research on masculinity and coal mining. Toni is an excellent interviewer.

You can listen to the episode here.

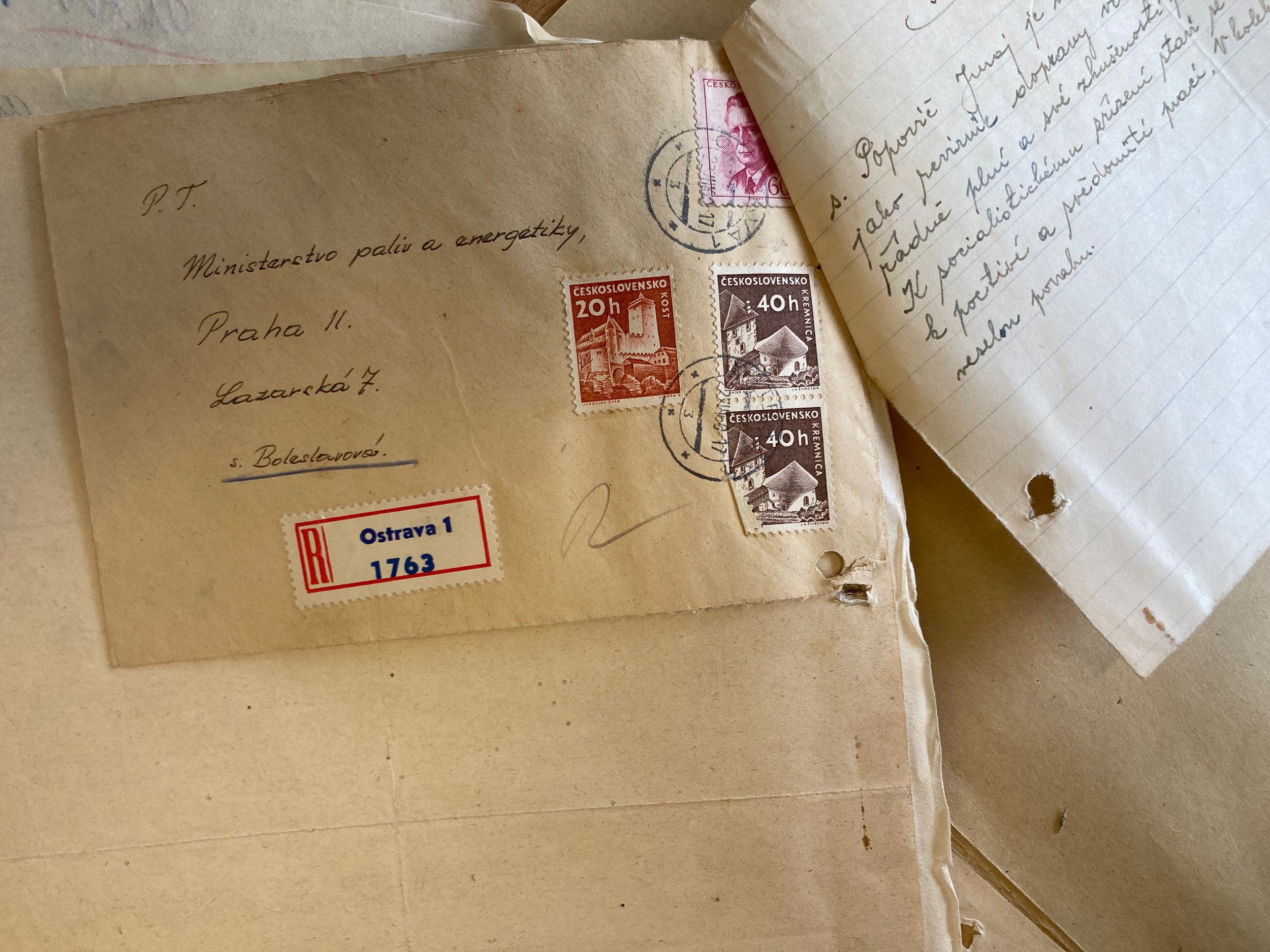

Among other topics, we discuss the Kosmos campground in Bulgaria which was formerly a resort for Czechoslovak coal miners. The photos below show mining families at Kosmos in the 1970s. These photos come from box 617 in the collection “Federální ministerstvo paliv a energetiky” in the National Archives of the Czech Republic.

Presenting at the Modern Europe & Environmental Studies Workshops at UChicago

I’m looking forward to presenting at a special joint session of the University of Chicago’s Transnational Approaches to Modern Europe Workshop and Committee on Environment, Geography and Urbanization Colloquium tomorrow afternoon. It’s always great to share works in progress with an interdisciplinary group. I will be presenting a chapter of my dissertation on the privatization of Czechoslovakia’s coal mines and the consequences of the transition to capitalism for mining masculinity.

Here is an abstract of the chapter:

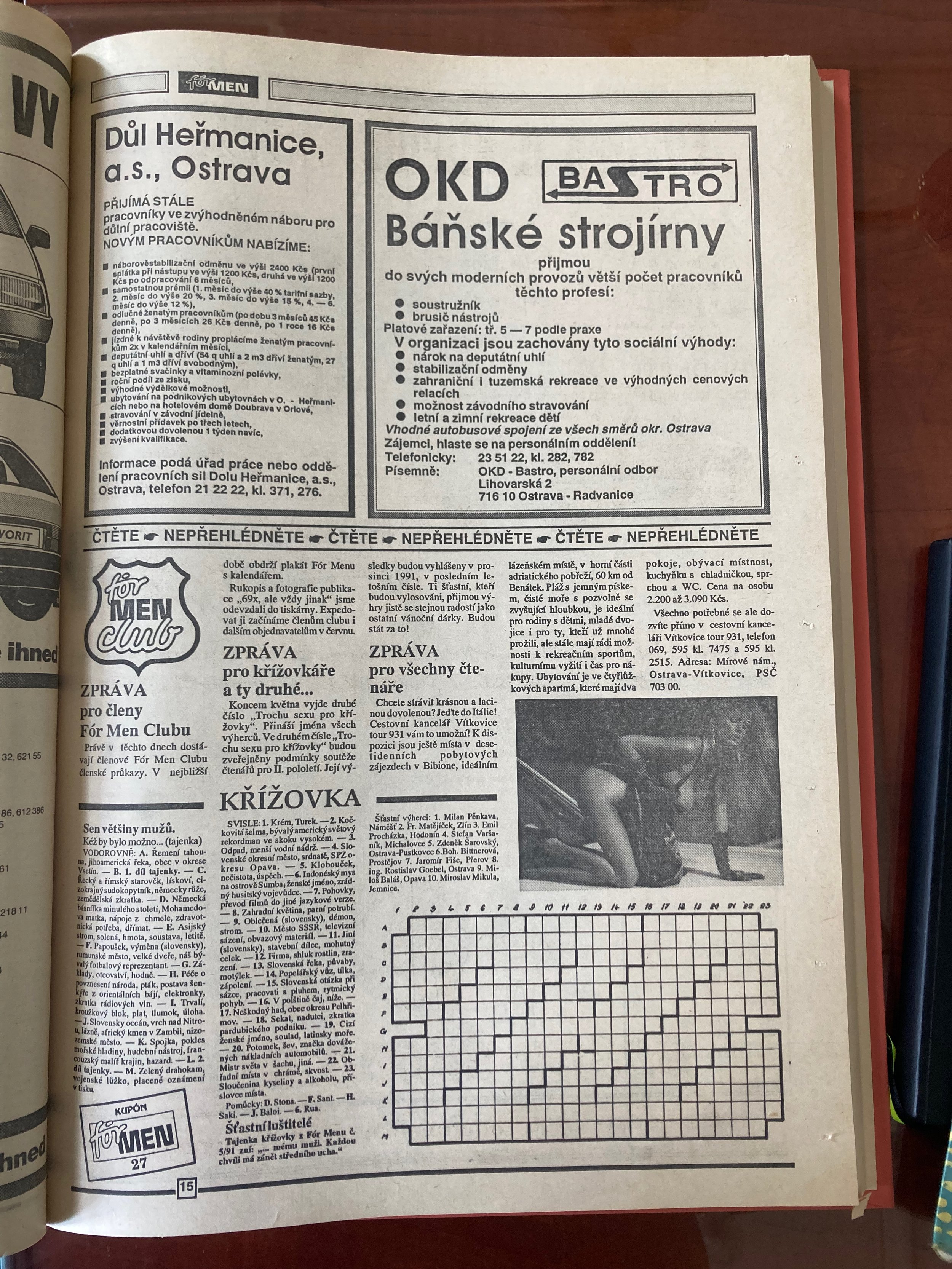

The post-socialist period in East Central Europe was a period of rapid energy transition. From 1948-1989, states in this region relied almost exclusively on domestic coal for industrial and residential heating and electricity, in the process transforming their mining regions into some of the most toxic environments in the world. After 1989, as newly elected governments and foreign economic advisers privatized state industries through a process of “shock therapy,” wealthy investors bought majority shares in coal mining enterprises and shuttered many mines deemed unprofitable. Using records from the corporate archives of the successor company to the state’s largest coal enterprise, this paper traces the privatization process in Czechoslovakia/Czech Republic as an emblematic case study in social consequences of de-carbonization for energy workers. Under socialism, the state coal mining enterprise was sprawling; hundreds of houses, tens of thousands of apartments, dozens of cafeterias, clinics and hospitals, laundries, recreation centers, hotels, bus depots, dormitories, a travel agency, and even a seaside campground in Bulgaria, all available for free or at extremely low cost to energy workers and their families. The mine’s post-1989 owners concluded that these services must be “converted to a profit-making basis” and, in the process, transformed from rights to commodities.

This paper argues that the privatization process forced government officials, foreign economic advisers, and miners to resolve deep ontological questions: What is a coal mine? Who is a coal miner? Each group had a different answer arising from their divergent assumptions of what elements of the economy and human behavior are “natural.” Miners rejected the idea that economic competition is a natural human (and, indeed, manly) endeavor, arguing instead that “every man naturally seeks certainty in all spheres of life.” This paper treats the process of de-carbonization in post-socialist Czechoslovakia as an ambiguous transition. Cleaner energy and a healthier environment came yoked to new and profound uncertainty for energy workers, in which services workers had long taken as their right—housing, light, heat, leisure, medical care—became governed by the market. In the process, unemployment, homelessness, and poverty, once unimaginable to energy workers, became common.

End of summer, change is afoot

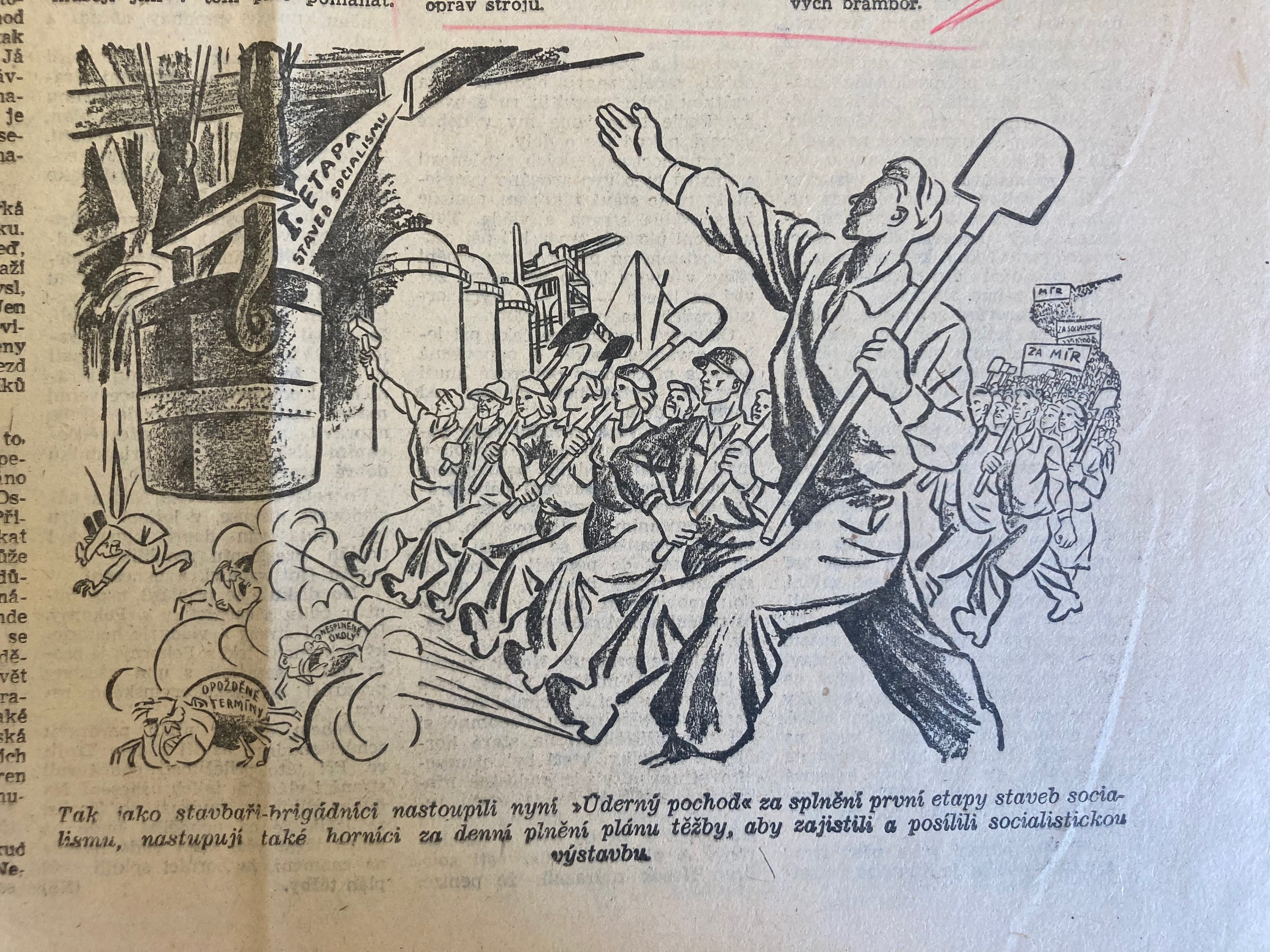

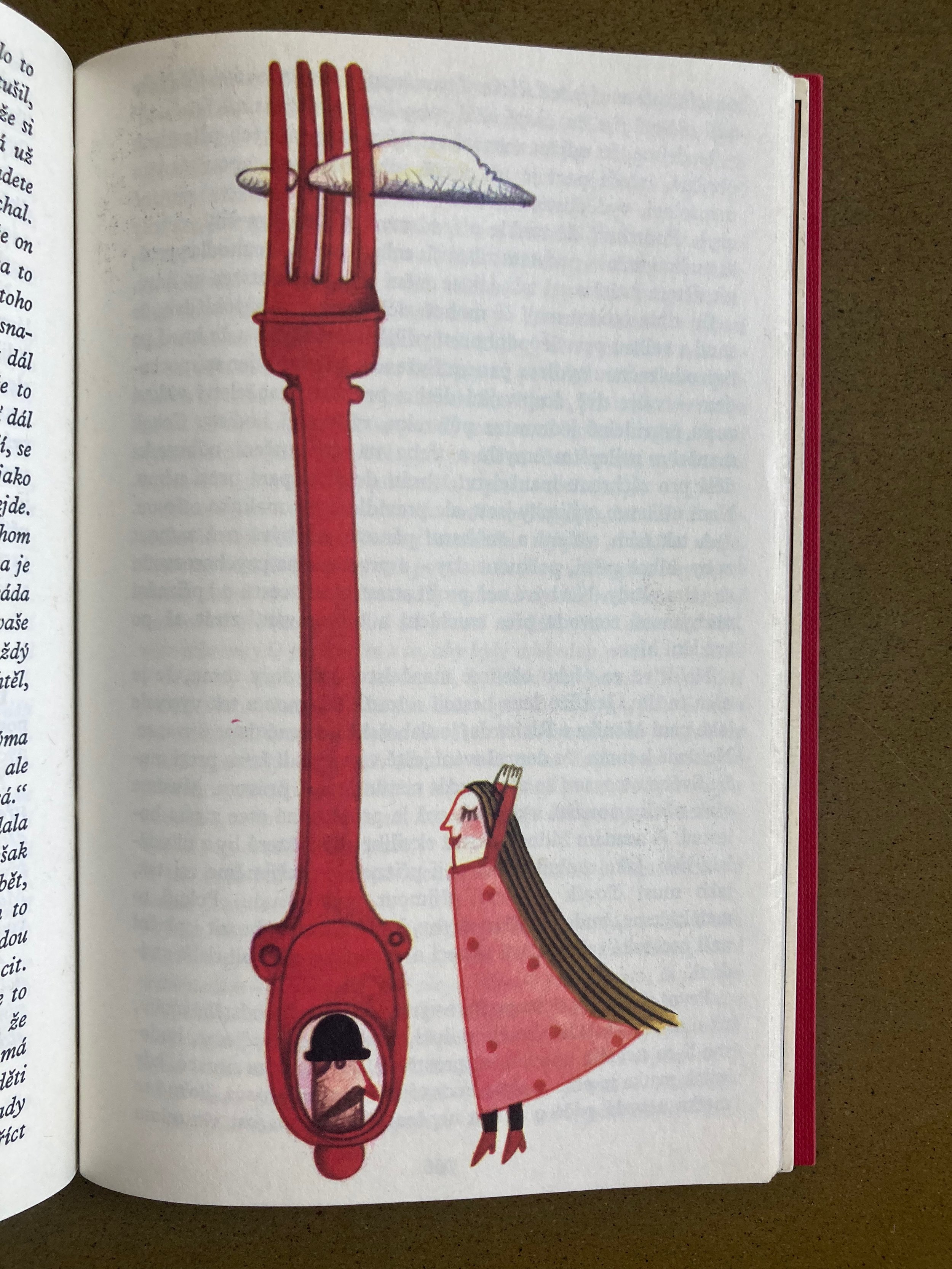

As summer winds down, I am working away on the section of my dissertation about post-socialism and the deindustrialization of Czechoslovakia/Czech Republic’s coal regions during the 1990s. I am continually struck by what a profound, personal change the transition to capitalism was for many people. How could you wrap your head around the intrinsic uncertainty of markets when you are plunged into them in adulthood? This cartoon, published in the newspaper Zdař bůh run by Ostrava’s coal mining labor union, really illustrates the whirlwind unthinkability of privatization:

The little girl is saying, “Grandpa, Grandpa, tell me a story.” Grandpa replies, “Which one, Mařenka, which one? The one about Silly Jack?” “No, Grandpa,” she replies, “the one about voucher privatization.”

BASEES 2023

It was a joy to go to Glasgow, Scotland last April for the meeting of the British Association of Slavonic and East European Studies. I was on a panel with Kristen Ghodsee and Anna Dobrowolska about the material culture of late socialism. I presented on Czechoslovak TVs, Kristen presented on Yugoslav typewriters, and Anna presented on Polish erotica. We also took the time to explore the region, paying a visit to the site of Robert Owen’s original intentional community at New Lanark.

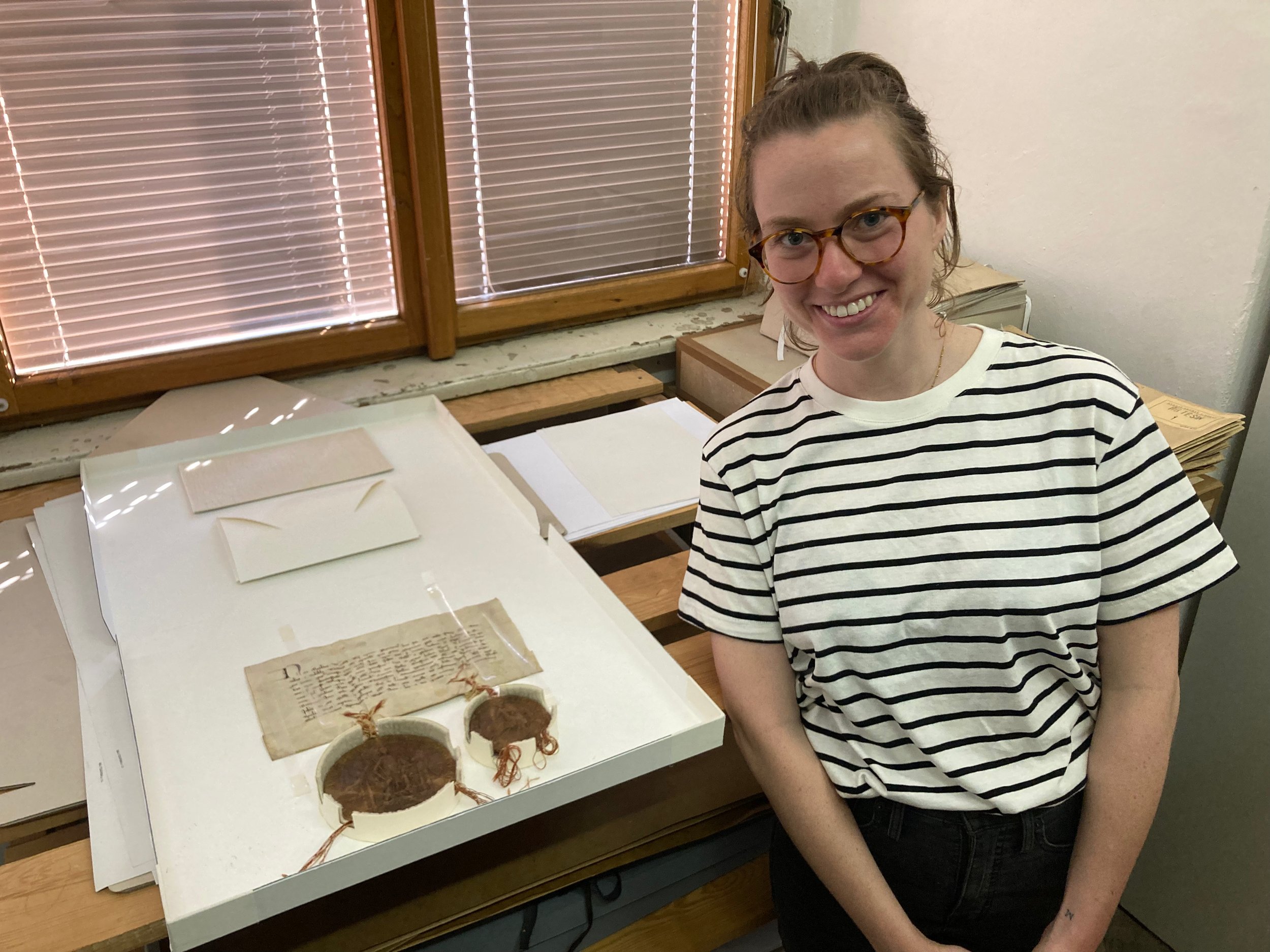

Quick Research Trip in June

Earlier this summer I made a month long research trip to the Czech Republic and Poland. It was so satisfying to be back in the archives after writing a good chunk of my dissertation. I knew what I was looking for and felt focused. Nevertheless, I still encountered some surprises!

Actually Existing Podcast Interview

It was a real pleasure to speak with Toni Harrison of the Actually Existing Socialism podcast back in April for an episode on socialism and women’s emancipation. You can listen to that interview here.

"What has socialism ever done for women?" in Spanish

I was pleased to learn a few months ago that an article I wrote with Kristen Ghodsee, my undergraduate mentor at Bowdoin College, for Catalyst “What Has Socialism Ever Done for Women?” has been translated into Spanish with the title ¿Qué ha hecho el socialismo por las mujeres?. Thanks to all who made this possible!

Fulbright in the Czech Republic

I was very pleased to spend the 2021-2022 academic year in the Czech Republic conducting archival research for my dissertation with the support of a Fulbright student grant. A few months back I reflected on my time there and the everyday life of archival work. In the words of one of my wonderful committee members, it can be “hard, lonely, and often deeply tedious,” but it is rewarding, and having come out the other end I can see that tedium has some advantages.

Here is a link to my Fulbright blog.

Environmental History Now

I wrote this piece for Environmental History Now over the winter about what we can learn from Czech coal mine reclamation.

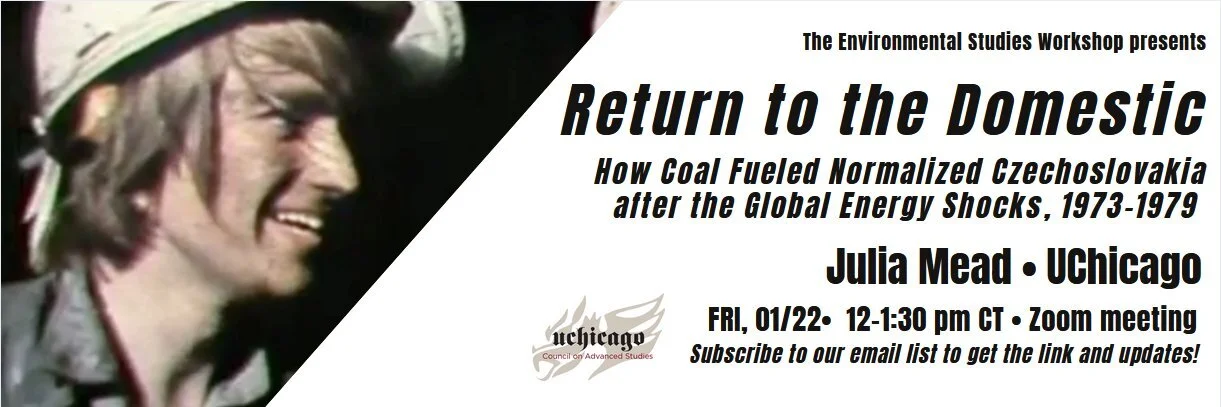

Environmental Studies Workshop

I am very pleased to be presenting at the University of Chicago’s interdisciplinary Environmental Studies Workshop on January 22, 2021, 12pm central time.

Books That Stuck 2020

I read more books in the year 2020 than in any previous year of my life, and I probably will never top it. This is because in October I took my qualifying exams for my PhD. Some of those books I found boring, many I skimmed, but some changed the way I think profoundly. I also was able to read some fiction. I think of it like dinner stomach and dessert stomach. Surely everyone who used to be a kid knows what this means. After you finish dinner you're full, but you still have room for dessert because of dessert stomach. I've got scholarship brain and novel brain. There's always room left in novel brain.

These are nine books I read last year that changed how I think. Some are classics, some are new, all are worth it.